About ten miles to the south-east of Woodcroft lies the picturesque village of Hamsterley. It was here that in 1587 William Blackett was born. William was the great-grandson of Nicholas Blackett of Woodcroft, but descended from Nicholas via a cadet (i.e. through younger sons) branch of the family. Whilst not therefore enjoying the social standing of his Woodcroft relatives, William nevertheless seems to have done reasonably well for himself, having moved away from Hamsterley to Gateshead some time after the birth of his eldest son, and pursued a moderately successful career as a manager or agent, enabling him to apprentice his two younger sons to wealthy Newcastle merchants. He could not have guessed, however, that through his eldest son, Christopher, would emerge a descendant who would play a major part in the development of railways (see Railway Blacketts), nor that through his youngest son William would emerge not one, but two baronetcies and a business empire that would dominate Newcastle and the surrounding area for more than a century.

Even harder to imagine was that a descendant of William junior would one day become Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. That descendant was William junior's 6xgreat-grandson, Anthony Eden.

William junior was born in 1621 in Jarrow, Co. Durham. His fortune, according to an old family legend, derived from a speculation in flax (used in the making of linen) and is recounted by John Straker in Pedigree of the Family of Blackett (Newcastle Typographical Society 1829) as follows:

Sir William, soon after he commenced business, risked his little all, in a speculation in flax, and having freighted a large vessel with that article, received the unpleasant intelligence that the flax fleet had been dispersed in a storm, and most of the vessels either lost or afterwards captured by the enemy. He took his accustomed walk next morning, ruminating on his supposed loss, and unconscious how far he was going, when on a sudden, he was aroused, by the noise of a ship on the river: he jumped upon an adjoining hedge, hailed the vessel, and found it to be his own, which had miraculously weathered the storm, and with difficulty had gained the port. He instantly returned, and hiring a horse, rode in a very short time to London, and hastening to the Exchange, found the merchants in great alarm about the loss of the flax fleet, and speaking of the consequently high price of flax. On informing them that he dealt in that article, and had a large quantity to dispose of, speculators soon flocked around him, and he sold his whole cargo at a most extravagant price, and the produce of that adventure laid the foundation for one of the largest fortunes acquired in Newcastle.

The story gave rise to the title of A. W. Purdue’s “The Ship that Came Home: The Story of a Northern Dynasty”, published in 2004, and there seems little doubt that the events described did actually occur. The reference to vessels "lost or afterwards captured by the enemy" dates the event to the first Anglo-Dutch war of 1652 to 1654, less than ten years after William had finished his apprenticeship. However, the conclusion that this event was the foundation of the vast enterprise that Blackett created, may not be so sound. The phrase "risked his little all" in the first sentence of the article perhaps gives some indication of his financial position at the time. He may have made a handsome profit on his flax, but the reason for the episode assuming such great and lasting importance to him could equally have been the financial calamity that could have fallen on him if the speculation had gone wrong. He had probably bet his shirt (presumably a linen one) on the cargo, and had it been lost could have faced ruin and an early termination of his business career. (Please also see Greg Finch's more detailed article on this by clicking here.)

The business empire that William Blackett created was based not on flax, but on the exploitation of coal and lead, and the astonishing success he achieved was due to a number of factors and qualities. In the first place he married well. In 1645, shortly after completing his nine year apprenticeship he married Elizabeth Kirkley, the daughter of a successful Newcastle merchant. He no doubt acquired a great deal of business knowledge and experience from his involvement in the Kirkley family business, plus a network of useful connections, and this, together with his qualities of good business judgement, not being afraid to take a risk, and a meticulous attention to detail coupled with a focus on broad business strategy, perhaps explains his success. No doubt too, a certain amount of luck came into it.

Whatever the reasons, the results were spectacular. He got into lead and coal by buying up leases of estates across the north east, including around Hexham, the Allen Valley and even as far west as Cumberland and as far south as Weardale in County Durham. But it was not what was on the land that interested him - it was what lay beneath. The demand for lead in particular was soaring, as it was used in roofs, leaded windows, pipes and by the army, and William did not just dig it out of the ground - he opened his own smelting works, in an example of what would today be called vertical integration of his business. By the late 1600s his wage bill was enormous and when a shortage of coinage arose he got around the problem by minting his own copper coins, perhaps an early example of quantitative easing.

Unsurprisingly he was also active in public life, becoming Sheriff of Newcastle in 1660, Mayor in 1666, and Member of Parliament in 1673, following which he was made a baronet by King Charles II.

His wife, Elizabeth, was not to enjoy the title of Lady Blackett for long, as she died in 1674. The following year Sir William, as he had now become, married again, this time to a widow who had been born Margaret Cocke, a member of a wealthy Newcastle family. (A popular expression in Newcastle at the time was "as rich as Cocke's canny hinnies".)

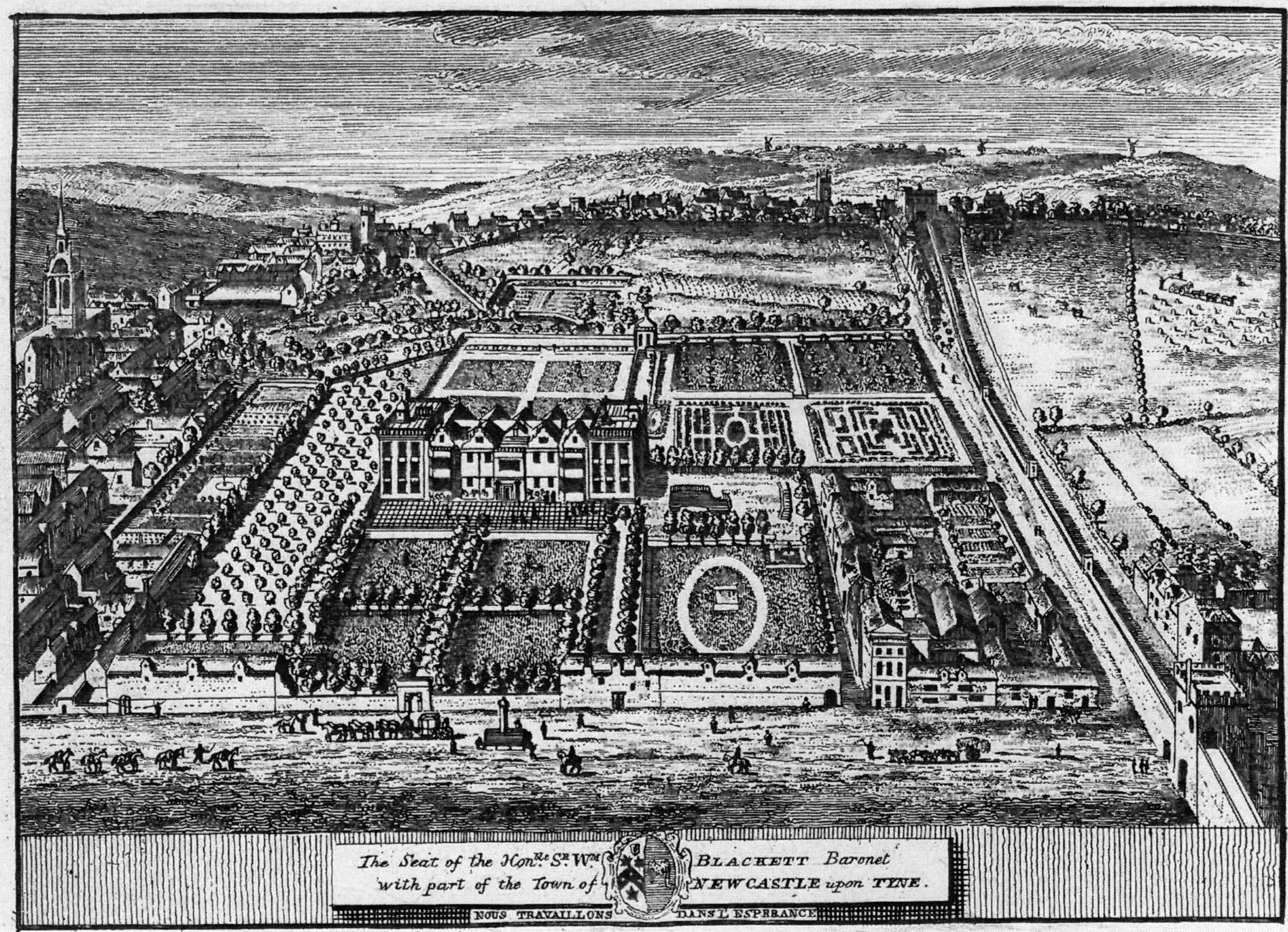

If William was good at making money, Margaret was good at helping him spend it. Until his marriage he had lived in The Close, an affluent part of Newcastle popular with merchants, but in 1675 he purchased Anderson Place, otherwise known as Newe House or Grey Friars, a vast mansion standing in twelve acres of grounds, all within the walls of Newcastle. He also took to riding around in a grand coach.

Despite his position and vast wealth he did not forget his family roots in Weardale. In 1674 he had adopted virtually the same coat of arms that his great-great uncle Thomas Blackett had registered almost 100 years earlier (see Coat of Arms ). Any doubt as to whether he, rather than the current Blackett owner of Woodcroft, was entitled to use them was overcome by Sir William making a generous donation to the College of Arms towards the rebuilding of their London headquarters.

And in 1676 he bought Woodcroft itself from his 3rd cousin, another William Blackett, who had fallen on hard times. His purchase of it was almost certainly based on sentiment, as there were no valuable mineral rights attaching to the property. He may well have been motivated by a wish to see the ancient Blackett home remain in the ownership of a Blackett, even the younger son of other younger sons, and possibly this may have motivated him into eventually leaving Woodcroft to his younger son.

The continuation of the first Blackett baronetcy

The baronetcy of course passed to Sir William's eldest son, Edward, and continues to this day, the title currently (as at 2024) being held by Sir Hugh Blackett, 12th Bt., who was until 2020 the owner of Matfen Hall. A number of other grand houses were owned over the years by the baronets of this line, including The Thorpe, Surrey Houses, Sockburn Hall, Halton Castle and Aydon Castle, and Newby Hall (see below).

Edward did not, however, inherit the bulk of his father's vast fortune. Although he was bequeathed a proportion of the vast business empire, the bulk of it was left to his younger brother, William, who was also appointed executor and received the residue of the estate, including Grey Friars and Woodcroft. (A third son, Michael, seems to have fallen out of favour with his father, and received a smaller inheritance.)

Edward had, however, received a substantial settlement on his marriage in 1674 to a wealthy heiress, and in 1690 he acquired Newby Hall, south east of Ripon in Yorkshire. It was already a grand house, but Edward set about rebuilding and extending it, under the guidance of Sir Christopher Wren. The works were said to have cost around £35,000, equivalent to about £7m in 2024 prices, a tidy sum, even for someone with Sir Edward's wealth. So what prompted him to expend that much at a time when his circumstances had not really changed? Well there was now a "new kid on the block" - his younger brother William, who had been made a baronet in his own right in 1685 and who was now extending the already massive Grey Friars by adding two new wings to it. The coincidence of timing does perhaps suggest that an element of filial competition had crept in, and Edward felt obliged to keep up with his younger brother.

William was of course able to spend lavishly as he had inherited the larger share of his father's estate. But what had prompted the first Sir William Blackett to leave the bulk of his business empire to his younger son William and not to the eldest son Edward? We can only speculate, but perhaps William senior saw in his younger son more of the risk-taking adventurous spirit that had enabled William to achieve such rapid growth of the business. If that growth were to continue, it needed more than the safe pair of hands that Edward would provide to keep the business ticking over. It needed more of a "Wild Bill" than a "Steady Eddie". As to whether that turned out to be a wise decision we shall see.

The second Blackett baronetcy

Things started out well for Sir William Blackett the younger. Unlike his elder brother he was firmly based in Newcastle and became mayor in 1683 and Member of Parliament in 1685, shortly after he had married the daughter of Sir Christopher Conyers, who brought with her a substantial dowry. And of course he was now Sir William Blackett of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne in the County of Northumberland (his father had omitted the words "Upon-Tyne" from his own title.) Like his father, he adopted a coat of arms based on those of the Woodcroft Blacketts.

Shortly after entering Parliament he managed to secure membership of the committee for the rebuilding of St. Paul's Cathedral, after the Great Fire of London, not a bad position for someone selling lead, as the roof of St. Paul's required 1,ooo tons of it.

A detailed account of the financial aspects of the business is contained in Greg Finch's excellent book, "The Blacketts". In summary, however, it is probably fair to say that William junior enjoyed mixed success at best. By his death in 1705 the gross value of the business had increased over the preceding 25 years, though that in part reflected increased land values. The net position was rather different, however, as the estate was saddled with substantial debts. Unlike his father, William had not been not growing a business from scratch, and it would have been unrealistic to expect the same exponential growth. In addition, although some of his ventures had been successful, he had his failures too, and overall he did not have the same huge amount of profit to plough back into the business to expand it. The expansion of the business was funded by borrowing.

His liquidity problems do not seem to have inhibited his spending. He gave generously to charity during his lifetime, and also by his will, which set up 'The Charity of Sir William Blackett the Younger', which still exists to this day. And he did not skimp on spending for himself. As we have seen, he added two new wings to Grey Friars, the Newcastle mansion, and in 1688 he acquired Wallington Hall from an impoverished Sir John Fenwick in exchange for taking over Fenwick's debts (a proportion of which were owed to Blackett anyway), plus an annuity of £2,000 a year to Fenwick and his wife. Poor Sir John Fenwick was not even able to enjoy this annuity for long. In 1696 he was sentenced to death for plotting to kill King William III. According to one reference, one of the MPs voting for the death penalty was Sir William Blackett. Job done.

Sir William died in 1705. He was succeeded by his 15 year old son, another William, who became Sir William Blackett, the second baronet of this line and technically the last, although appearances would turn out to be not quite so straightforward.

Unlike his father and grandfather, this Sir William had no business training or experience, and he inherited only one of their qualities - the ability to spend money. By the age of 23 he had fathered two illegitimate children by Elizabeth Ord, whose interests, it must be said, he never abandoned, particularly in respect of the surviving child, another Elizabeth, who will figure shortly. This was by no means his only indiscretion. In 1717 the daughter of Blackett's long-standing chief agent, John Wilkinson, disappeared. Her frantic father eventually succeeded in tracking her down to Boroughbridge in Yorkshire, where she was ensconced with Sir William Blackett. William initially denied seducing her, at least at first, but Wilkinson was not convinced and resigned his post. Sir William lost his chief agent and we can only speculate what the young lady lost.

The real trouble that Sir William got into, however, had occurred two years earlier at the time of the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715. The Scottish clans rose in support of the "Old Pretender", James Stuart, and parts of England supported them, including virtually the whole of Northumberland except for the town of Newcastle, which largely remained loyal to King George. Blackett was believed by many to be involved, but at first the Newcastle authorities hesitated to arrest him. After all he was a Blackett and was Member of Parliament for Newcastle, like his father and grandfather before him.

Eventually a warrant for his arrest was issued and Sir William went on the run. He may well have visited Wallington, and certainly turned up at his uncle's Newby mansion, but eventually he arrived at Esholt Hall in Yorkshire, the home of his brother-in-law, Sir Walter Calverley. This was hardly a stealthy operation: Sir William arrived in his ornate coach, accompanied by servants and a large amount of luggage. Unsurprisingly the authorities were hard on his heels, and they arrived the next morning. By then, however, Sir William had vanished. He had presumably been given a talking to by his brother-in-law, and fled disguised in ordinary countrymen's clothes, leaving his coach, servants and baggage behind, managing to reach London, where he hid until the heat died down. He had had a lucky escape but Sir Walter Calverley was not so fortunate and was dismissed from his position as Deputy Lord Lieutenant for aiding Blackett evade capture.

So was Sir William involved in the uprising? The answer is that nobody knows. After the leaders of the rebellion were captured they were interrogated separately and asked if Blackett was involved, but stoutly maintained that they simply did not know. The answer might possibly be that William simply chickened out. It was one thing for a twenty-five year old to pass his wine glass over the finger bowl during the loyal toast, thus signifying his support for "the king over the water", i.e. James Stuart, but when it came to actually joining in the uprising William thought better of it. He had too much to lose.

He managed to regain favour with the King fairly quickly, but the canny inhabitants of Newcastle took longer to win over. Eventually, however, he did so by spending money. He gave generously to charity and in 1725 on his marriage to a daughter of the Earl of Jersey he laid on so much alcoholic refreshment that much of the county was drunk for days. The Devil's Punchbowl at Shaftoe Crag was hollowed out and used as a drinking vessel (see The mother of all Blackett parties). At Hexham, the great bell of St. Mary's, weighing three tons, was rung with such gusto by drunken revellers that it cracked.

Perhaps because of his lifestyle Sir William died in 1728 at the age of 38. More than one thousand mourners joined his funeral procession through the streets of Newcastle. He left no legitimate heir and thus this second, short-lived baronetcy came to an end. Or at least it did technically.

For all his faults, Sir William was determined that his baronetcy would continue in appearance, if not in substance. Under the terms of his lengthy will the residue of the estate, including the business empire, was left in trust for his nephew, Walter Calverley, the son of his brother-in-law who had helped him evade capture thirteen years earlier, provided Walter married Blackett's illegitimate daughter, Elizabeth Ord, and changed his name to Blackett. Despite some initial reluctance from Elizabeth, Walter married her in 1729 and by a private Act of Parliament took the name of Blackett in 1734. On inheriting his father's own baronetcy in 1749, he became Sir Walter Calverley Blackett, increasingly shortened to Sir Walter Blackett.

Whether or not Sir William Blackett chose Walter because of the help he had received from Walter's father in 1715, Walter turned out to be a wise choice. Although by no means a good businessman, he had the sense to rely on dependable stewards to run the vast business empire for him, including his second cousin, John Erasmus Blackett, whom Sir Walter appointed in 1776.

Sir Walter was a character of contrasts. He split his time between Grey Friars in Newcastle and Wallington, which he purchased outright from the Blackett trust in 1750, and while at Wallington seems to have enjoyed the life of a simple country squire, often dressing in plain countrymen's clothes. Despite regularly complaining about lack of funds, however, he was not averse to spending, and carried out major improvements to Wallington, as well as giving generously to charity, including building a library at St. Nicholas's Church, Newcastle in 1736, endowing the Newcastle Infirmary in the 1750s, and building the colonnaded piazza in Hexham market square now known as The Shambles in 1766.

He was also active in public life, becoming a Newcastle alderman in 1729, Sheriff of Northumberland in 1731/32, and Mayor of Newcastle in 1735, 1748, 1756, 1764 and 1771. He was also Member of Parliament for Newcastle from 1734 to the time of his death in 1777, becoming the "Father of the House", i.e. the longest serving MP. All in all Sir William Blackett had made a wise choice.

Except for one thing. Walter's marriage to Elizabeth Ord was said to have not been a happy one and although he was reputed to 'spread his favours' widely around the county, he died without leaving a legitimate heir. The canny Sir William Blackett had, however, foreseen even this possibility in his lengthy will, and the estate and business was now to be held in trust for the eldest surviving son of Sir William's sister, Lady Diana Wentworth, provided that son change his name to Blackett, as Walter had done. Sir Thomas Wentworth duly obliged and became Sir Thomas Wentworth Blackett.

Unlike Sir Walter, he did not take an active role in Newcastle affairs, basing himself at Bretton Hall in Yorkshire, and retaining John Erasmus Blackett as chief steward to run the business. Sir Thomas died in 1792, leaving three illegitimate daughters but no legitimate male heir. Even the comprehensive terms of Sir William Blackett's will were not enough to engineer a continuation of the Blackett name in these circumstances, and with the death of Sir Thomas the appearance of this baronetcy came to and end. Diana Beaumont, the eldest of Sir Thomas's daughters, inherited much of the estate and business interests and several of her descendants over the next few generations were given a middle name of Blackett, the mining business becoming known as the Blackett-Beaumont Company.

One surviving Blackett connection to the business was its continuing chief steward, John Erasmus Blackett. When Sir Walter Blackett had asked him to take up the post in 1776 it would have been understandable if he had had mixed feelings. On the one hand he descended legitimately, albeit through younger sons, from the Sir William Blackett who had built the business, in contrast to his new employer, Sir Walter, who had acquired his interest in the business through marrying the illegitimate daughter of Sir William's younger son. Moreover, John Erasmus Blackett was already a figure of some importance in Newcastle, having already been mayor twice. On the other hand, John Erasmus Blackett had expensive tastes (even his son-in-law, Admiral Lord Collingwood, would later complain about his spending habits), and in addition to the remuneration he would receive, the position was one of prestige and influence. That did not however, prevent the haughty Diana Beaumont from snubbing at Court Blackett's daughter, Sarah Collingwood, then the wife of a young naval officer, declaring that she was merely the daughter of her steward. Some years later, again at Court, the now Lady Collingwood snubbed Mrs. Beaumont in turn. It was an expensive gesture, however, as Mrs. Beaumont at once sacked John Erasmus Blackett from his position, thus bringing to and end the ownership or management of the business empire by a Blackett.

For a list of the Blacketts of both baronetcies please see Blackett baronets.